Stanford scientists develop water splitter that runs on an ordinary AAA battery

Aug. 22, 2014

By Mark Shwartz

In 2015, American consumers will finally be able to purchase fuel cell cars from Toyota and other manufacturers. Although touted as zero-emissions vehicles, most of the cars will run on hydrogen made from natural gas, a fossil fuel that contributes to global warming.

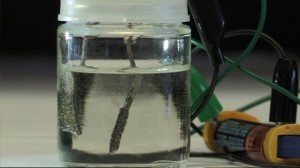

Now scientists at Stanford University have developed a low-cost, emissions-free device that uses an ordinary AAA battery to produce hydrogen by water electrolysis. The battery sends an electric current through two electrodes that split liquid water into hydrogen and oxygen gas. Unlike other water splitters that use precious-metal catalysts, the electrodes in the Stanford device are made of inexpensive and abundant nickel and iron.

Using nickel and iron, which are cheap materials, we were able to make the electrocatalysts active enough to split water at room temperature with a single 1.5-volt battery,” said Hongjie Dai, a professor of chemistry at Stanford. “This is the first time anyone has used non-precious metal catalysts to split water at a voltage that low. It’s quite remarkable, because normally you need expensive metals, like platinum or iridium, to achieve that voltage.”

In addition to producing hydrogen, the novel water splitter could be used to make chlorine gas and sodium hydroxide, an important industrial chemical, according to Dai. He and his colleagues describe the new device in a study published in the Aug. 22 issue of the journal Nature Communications.

The promise of hydrogen

Automakers have long considered the hydrogen fuel cell a promising alternative to the gasoline engine. Fuel cell technology is essentially water splitting in reverse. A fuel cell combines stored hydrogen gas with oxygen from the air to produce electricity, which powers the car. The only byproduct is water – unlike gasoline combustion, which emits carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas.

Earlier this year, Hyundai began leasing fuel cell vehicles in Southern California. Toyota and Honda will begin selling fuel cell cars in 2015. Most of these vehicles will run on fuel manufactured at large industrial plants that produce hydrogen by combining very hot steam and natural gas, an energy-intensive process that releases carbon dioxide as a byproduct.

Splitting water to make hydrogen requires no fossil fuels and emits no greenhouse gases. But scientists have yet to develop an affordable, active water splitter with catalysts capable of working at industrial scales.

“It’s been a constant pursuit for decades to make low-cost electrocatalysts with high activity and long durability,” Dai said. “When we found out that a nickel-based catalyst is as effective as platinum, it came as a complete surprise.”

Saving energy and money

The discovery was made by Stanford graduate student Ming Gong, co-lead author of the study. “Ming discovered a nickel-metal/nickel-oxide structure that turns out to be more active than pure nickel metal or pure nickel oxide alone,” Dai said. “This novel structure favors hydrogen electrocatalysis, but we still don’t fully understand the science behind it.”

The nickel/nickel-oxide catalyst significantly lowers the voltage required to split water, which could eventually save hydrogen producers billions of dollars in electricity costs, according to Gong. His next goal is to improve the durability of the device.

“The electrodes are fairly stable, but they do slowly decay over time,” he said. “The current device would probably run for days, but weeks or months would be preferable. That goal is achievable based on my most recent results.”

The researchers also plan to develop a water splitter than runs on electricity produced by solar energy.

“Hydrogen is an ideal fuel for powering vehicles, buildings and storing renewable energy on the grid,” said Dai. “We’re very glad that we were able to make a catalyst that’s very active and low cost. This shows that through nanoscale engineering of materials we can really make a difference in how we make fuels and consume energy.”

Other authors of the study are Wu Zhou, Oak Ridge National Laboratory (co-lead author); Mingyun Guan, Meng-Chang Lin, Bo Zhang, Di-Yan Wang and Jiang Yang, Stanford; Mon-Che Tsai and Bing-Joe Wang, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology; Jiang Zhou and Yongfeng Hu, Canadian Light Source Inc.; and Stephen J. Pennycook, University of Tennessee.

Principal funding was provided by the Global Climate and Energy Project (GCEP) and the Precourt Institute for Energy at Stanford and by the U.S. Department of Energy.

This article was originally published in the Stanford Report.

Posted by permission