January 22, 2016

It is still three minutes to midnight

Lynn Eden, Robert Rosner, Rod Ewing, Lawrence M. Krauss, Sivan Kartha, Thomas R. Pickering, Raymond T. Pierrehumbert, Ramamurti Rajaraman, Jennifer Sims, Richard C. J. Somerville, Sharon Squasson, David Titley

From: The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Science and Security Board

To: Leaders and citizens of the world

Re: It is still three minutes to midnight

In the past year, the international community has made some positive strides in regard to humanity’s two most pressing existential threats, nuclear weapons and climate change. In July 2015, at the end of nearly two years of negotiations, six world powers and Iran reached a historic agreement that limits the Iranian nuclear program and aims to prevent Tehran from developing nuclear weaponry. And in December of last year, nearly 200 countries agreed in Paris to a process by which they will attempt to reduce their emissions of carbon dioxide, aiming to keep the increase in world temperature well below 2.0 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial level.

The Iran nuclear agreement and the Paris climate accord are major diplomatic achievements, but they constitute only small bright spots in a darker world situation full of potential for catastrophe.

Even as the Iran agreement was hammered out, tensions between the United States and Russia rose to levels reminiscent of the worst periods of the Cold War. Conflict in Ukraine and Syria continued, accompanied by dangerous bluster and brinkmanship, with Turkey, a NATO member, shooting down a Russian warplane involved in Syria, the director of a state-run Russian news agency making statements about turning the United States to radioactive ash, and NATO and Russia repositioning military assets and conducting significant exercises with them. Washington and Moscow continue to adhere to most existing nuclear arms control agreements, but the United States, Russia, and other nuclear weapons countries are engaged in programs to modernize their nuclear arsenals, suggesting that they plan to keep and maintain the readiness of their nuclear weapons for decades, at least—despite their pledges, codified in the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, to pursue nuclear disarmament.

Promising though it may be, the Paris climate agreement came toward the end of Earth’s warmest year on record, with the increase in global temperature over pre-industrial levels surpassing one degree Celsius. Voluntary pledges made in Paris to limit greenhouse gas emissions are insufficient to the task of averting drastic climate change. They are, at best, incremental moves toward the fundamental change in world energy systems that must occur, if climate change is to ultimately be arrested.

Because the diplomatic successes on Iran and in Paris have been offset, at least, by negative events in the nuclear and climate arenas, the members of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Science and Security Board find the world situation to be highly threatening to humanity—so threatening that the hands of the Doomsday Clock must remain at three minutes to midnight, the closest they’ve been to catastrophe since the early days of above-ground hydrogen bomb testing.

Last year, we wrote that world leaders had failed to act with the speed or on the scale required to protect citizens from the danger posed by climate change and nuclear war, and that those failures endangered every person on Earth. In keeping the hands of the Doomsday Clock at three minutes to midnight, the members of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Science and Security Board mean to make a clear statement: The world situation remains highly threatening to humanity, and decisive action to reduce the danger posed by nuclear weapons and climate change is urgently required.

A promising Iran agreement within a dangerous nuclear situation. The year 2015 abounded in disturbing nuclear rhetoric, particularly about the usability of nuclear weapons, but contained at least one real achievement: the landmark Iran nuclear deal. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) that the United States, China, Russia, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom reached with Iran in July 2015 ends several decades of uncertainty about Tehran’s nuclear capabilities. The agreement will test the resolve of all parties to move forward and build trust, but it has the potential to transform the nuclear nonproliferation landscape in the Middle East as well as provide impetus for sorely needed innovations in the nonproliferation regime. The JCPOA covered the bases, capping the numbers and kinds of uranium-enrichment centrifuges Iran can possess, placing limits on that country’s stockpile of enriched uranium, and converting the sensitive Fordow facility into a research center. The agreement also irreversibly transforms Iran’s Arak research reactor so Iran cannot produce and retain plutonium. The inclusion of long-term monitoring of Iran’s uranium and other nuclear supply chains will strengthen confidence that Iran has no clandestine sites. A credible effort to monitor Iran’s compliance with the accord could demonstrate new technologies and approaches for reducing the risks of nuclear proliferation.

The ability of key nuclear weapon states to cooperate on nuclear non-proliferation is one of the few bright spots in the world nuclear landscape; the United States and Russia continue to make reductions in deployed nuclear warheads under the new START treaty. But nuclear modernization programs—designed to maintain capabilities for the next half-century—also proceed apace. The Russians will have fewer launchers, but their future force will be more mobile and have more flexibly targeted warheads. The United States plans to spend $350 billion in the next 10 years to maintain and modernize its nuclear forces and infrastructure, despite rhetoric about a nuclear weapons-free world. With no follow-on arms control agreement in sight and deeply disturbing nuclear rhetoric issuing from Russia, the risks of short launch times, of large warhead stockpiles, and of narrowing channels for averting crisis recall the dark days of the Cold War.

Conflict over free passage in the South China Sea is another worrisome development. China’s territorial claims to islands there—some of which it has enlarged for military purposes—are contested primarily by countries in the region. But as legally justifiable as they may be, recent US efforts to assert a right of free passage in the South China Sea by sending a naval vessel and airplanes close to those islands have the potential to escalate into major conflict between nuclear powers.

The prospects for nuclear arms control beyond the United States and Russia are, in the near term, unfavorable. China, Pakistan, India, and North Korea are all increasing their nuclear arsenals, albeit at different rates. China’s recent agreement to help Pakistan build nuclear missile submarine platforms is a matter of concern, but probably less so than other developments in Pakistan’s arsenal, including improvements to its ballistic missiles and air-launched cruise missiles and its aggressive rhetoric regarding the use of tactical nuclear weapons to “de-escalate” a conventional conflict (rhetoric that is unfortunately similar to Russia’s own “de-escalation” doctrine). Meanwhile, North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un announced at the end of the year that his country had developed a hydrogen bomb and followed through with a test on January 5, 2016. So far, experts assess that it likely was not a two-stage thermonuclear weapon, but there is little doubt that North Korea will continue to develop its nuclear arsenal in the absence of restraints.

The world may be used to outrageous rhetoric from North Korea, but officials in several other countries made irresponsible comments in 2015 about raising the alert status of nuclear weapon systems, acquiring nuclear capabilities, and even using nuclear weapons. We hope that, as an unintended consequence of such rhetoric, citizens will be galvanized to address risks they thought long contained. The more likely outcome is that nuclear bombast will raise the temperature in crisis situations. The maintenance of peace requires that nuclear rhetoric and actions be tamped down.

A mixed response to climate change. The year 2015 was one of mixed developments in regard to the threat of global warming. Global mean carbon dioxide concentrations passed 400 parts per million, with global mean warming since pre-industrial times exceeding 1 degree Celsius for the first time. These developments underscore the continued inadequacy of efforts to control the greenhouse gas emissions that are causing climate change.

There have been some positive developments, however, notably the agreement in Paris among 196 countries on a global climate accord. Boldly setting a goal of keeping global mean warming well below 2 degrees Celsius, the agreement recognizes the need to bring net greenhouse gas emissions to zero before the end of the century. Still, it is unclear how the world will actually meet that goal. The backbone of the accord—pledges submitted by each of the signatory countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions—is far from sufficient. Even while acclaiming the Paris agreement as a landmark achievement, the UN Climate Change Secretariat acknowledged that if all countries fulfill their voluntary commitments but do no more than that, then by 2025, the world will have used half of the remaining carbon dioxide budget consistent with a 2 degrees C goal. Three-quarters of that budget of carbon emissions will have been exhausted by 2030. And this assessment assumes that countries will fully comply with their pledges—even though the Paris agreement includes no effective enforcement mechanisms to assure that countries do so.

Success in limiting climate change will ultimately depend on the good faith and good will of the signatories, and their willingness to cut emissions even more than they have pledged and to make even deeper cuts over time; most of the emissions pledges now are set to end sometime between 2025 and 2030. Still, the accord represents an encouraging step forward in that it will get the world off its current path of exponentially growing emissions, which is the first step toward stabilizing the climate. Importantly, the pledges by developing countries, notably China, include serious mitigation efforts that in the aggregate exceed those of the developed countries. These pledges recognize that solving the climate problem requires the developing world to get on a low-carbon pathway compatible with its development needs, even though the climate has been brought to its present perilous state primarily through the past emissions of the developed world.

Other positive developments include the Papal encyclical Laudato Si, which cogently and powerfully expresses the moral imperative to restrain the human impact on climate; the growing number of corporations, educational institutions, faith-based groups, and institutional investors that have demonstrated their commitment to sustainability through disinvestment in fossil fuel companies; and the emergence of bold, on-the-ground initiatives to leapfrog to more sustainable energy systems. The elections of more climate-friendly governments in Canada and Australia are also encouraging, but must be seen against the steady backtracking of the United Kingdom’s present government on climate policies and the continued intransigence of the Republican Party in the United States, which stands alone in the world in failing to acknowledge even that human-caused climate change is a problem.

Given the mixed nature of the year’s developments regarding protection of the climate, we find no climate-related justification for a change in the setting of the Doomsday Clock.

The nuclear power leadership vacuum. Nuclear energy provides slightly more than 10 percent of the world’s electricity-generating capacity, and some countries—notably China and several countries in the Middle East—have announced ambitious programs to expand their nuclear capacity, for a host of reasons, including the need to respond to growing energy demands and to address climate change. But the international community has not developed coordinated plans to meet cost, safety, radioactive waste management, and proliferation challenges that large-scale nuclear expansion poses.

Nuclear power is growing in some regions that can afford its high construction costs, sometimes in countries that do not have adequately independent regulatory systems. Meanwhile, several countries continue to show interest in acquiring technologies for uranium enrichment and spent fuel reprocessing—technologies that can be used to create weapons-grade fissile materials for nuclear weapons. Stockpiles of highly radioactive spent nuclear fuel continue to grow (globally, about 10,000 metric tons of heavy metal are produced each year). Spent fuel requires safe geologic disposal over a time scale of hundreds of thousands of years.

The US programs for handling waste from defense programs, for dismantling nuclear weapons, and for storing commercially generated spent nuclear fuel continue to flounder. Large projects—including a mixed-oxide fuel-fabrication plant at the Savannah River Site, meant to blend surplus weapons-grade plutonium with uranium so it can be used in commercial nuclear power plants—fall ever further behind schedule, and costs continue to mount, with the US Energy Department spending some $5.8 billion each year on environmental management of legacy nuclear waste from US weapons programs.

Because of such problems, in the United States and in other countries, nuclear power’s attractiveness as an alternative to fossil fuels has decreased, despite the clear need for carbon-emissions-free energy in the age of climate change.

More attention to emerging technological threats. The fast pace of technological change makes it incumbent on world leaders to pay attention to the control of emerging science that could become a major threat to humanity.

It is clear that advances in biotechnology; in artificial intelligence, particularly for use in robotic weapons; and in the cyber realm all have the potential to create global-scale risk. The Bulletin continues to be concerned about the lag between scientific advances in dual-use technologies and the ability of civil society to control them. The Science and Security Board now repeats the advice it gave last year: The international community needs to strengthen existing institutions that regulate emergent technologies and to create new forums for exploring potential risks and proposing potential controls on those areas of scientific and technological advance that have so far been subject to little if any societal oversight.

Three minutes is too close. Far too close. We, the members of the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, want to be clear about our decision not to move the hands of the Doomsday Clock in 2016: That decision is not good news, but an expression of dismay that world leaders continue to fail to focus their efforts and the world’s attention on reducing the extreme danger posed by nuclear weapons and climate change. When we call these dangers existential, that is exactly what we mean: They threaten the very existence of civilization and therefore should be the first order of business for leaders who care about their constituents and their countries.

We recognize that some progress has been made on the nuclear and climate fronts. We hail the Paris climate accord and the Iran nuclear agreement as real diplomatic achievements that required genuine political leadership. But those two accomplishments are far from sufficient to address the daunting array of major threats the world faces. A new Cold War looms, with absolutely insupportable, extraordinarily expensive, extremely shortsighted nuclear “modernization” programs continuing apace around the world. Paris notwithstanding, the fight against climate change has barely begun, and it is unclear that the nations of the world are ready to make the many hard choices that will be necessary to stabilize the climate and avert possible environmental disasters.

Because of failures in world leadership during 2015, we see that the recommendations for action in last year’s Doomsday Clock announcement are, very unfortunately, at least as relevant today as they were a year ago, and that the North Korean situation requires renewed focus. We therefore call on the citizens of the world to demand that their leaders:

● Dramatically reduce proposed spending on nuclear weapons modernization programs. The United States and Russia have hatched plans to essentially rebuild their entire nuclear triads in coming decades, and other nuclear weapons countries are following suit. The projected costs of these “improvements” to nuclear arsenals are indefensible, and they undermine the global disarmament regime.

● Re-energize the disarmament process, with a focus on results. The United States and Russia, in particular, need to start negotiations on shrinking their strategic and tactical nuclear arsenals. The world can be more secure with much, much smaller nuclear arsenals than now exist—if political leaders are truly interested in protecting their citizens from harm.

● Engage North Korea to reduce nuclear risks. Neighbors in Asia face the most urgent threat, but as North Korea improves its nuclear and missile arsenals, the threat will rapidly become global. Now is not the time to tighten North Korea’s isolation but to engage seriously in dialogue.

● Follow up on the Paris accord with actions that sharply reduce greenhouse gas emissions and fulfill the Paris promise of keeping warming below 2 degrees Celsius.The 2-degree-above-pre-industrial-levels target is consistent with consensus views on climate science and is eminently achievable and economically viable, providing poorer countries are given the support they need to make the post-carbon transition and to weather the impacts of the warming that is now unavoidable.

● Deal now with the commercial nuclear waste problem. Reasonable people can disagree on whether an expansion of nuclear-powered electricity generation should be a major component of the effort to limit climate change. Regardless of the future course of the worldwide nuclear power industry, there will be a need for safe and secure interim and permanent nuclear waste storage facilities.

● Create institutions specifically assigned to explore and address potentially catastrophic misuses of new technologies. Scientific advance can provide society with great benefits, but the potential for misuse of potent new technologies is real, and government, scientific, and business leaders need to take appropriate steps to address possible devastating consequences of these technologies.

Last year, the Science and Security Board moved the Doomsday Clock forward to three minutes to midnight, noting: “The probability of global catastrophe is very high, and the actions needed to reduce the risks of disaster must be taken very soon.” That probability has not been reduced. The Clock ticks. Global danger looms. Wise leaders should act—immediately.

Doomsday Clock Statement

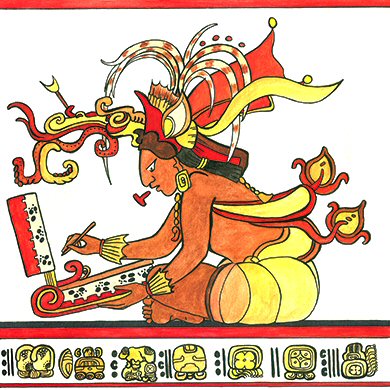

The Mayan Lesson

The Mayan Lesson

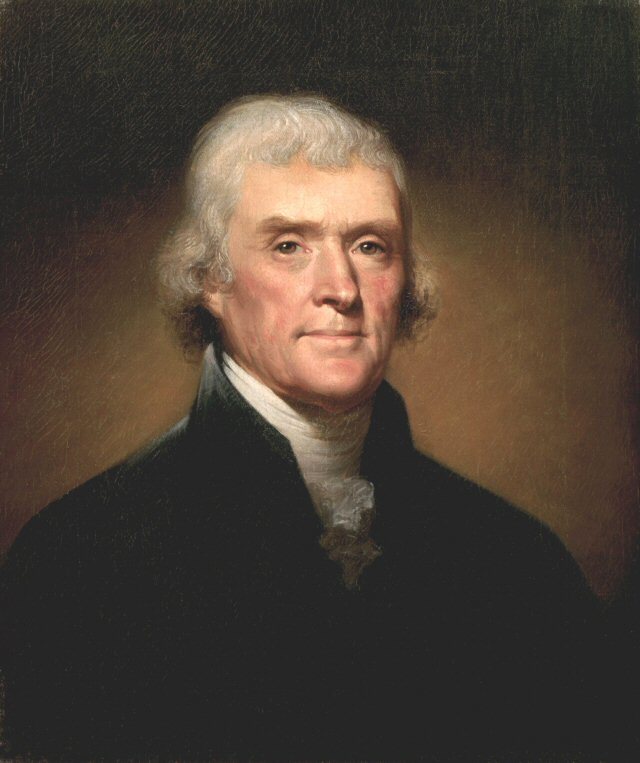

From 2007 into 2009, Evgeny Primakov and I chaired a group composed of retired senior ministers, high officials, and military leaders from Russia and the United States, including some of you present here today. Its purpose was to ease the adversarial aspects of the U.S.-Russian relationship and to consider opportunities for cooperative approaches. In America, it was described as a Track II group, which meant it was bipartisan and encouraged by the White House to explore but not negotiate on its behalf. We alternated meetings in each other’s country. President Putin received the group in Moscow in 2007, and President Medvedev in 2009. In 2008, President George W. Bush assembled most of his National Security team in the Cabinet Room for a dialogue with our guests.

From 2007 into 2009, Evgeny Primakov and I chaired a group composed of retired senior ministers, high officials, and military leaders from Russia and the United States, including some of you present here today. Its purpose was to ease the adversarial aspects of the U.S.-Russian relationship and to consider opportunities for cooperative approaches. In America, it was described as a Track II group, which meant it was bipartisan and encouraged by the White House to explore but not negotiate on its behalf. We alternated meetings in each other’s country. President Putin received the group in Moscow in 2007, and President Medvedev in 2009. In 2008, President George W. Bush assembled most of his National Security team in the Cabinet Room for a dialogue with our guests. “I can’t believe that this world can go on beyond our generation and on down to succeeding generations with this kind of weapon on both sides poised at each other without someday some fool or some maniac or some accident triggering the kind of war that is the end of the line for all of us. And I just think of what a sigh of relief would go up from everyone on this earth if someday–and this is what I have–my hope, way in the back of my head–is that if we start down the road to reduction, maybe one day in doing that, somebody will say, ‘Why not all the way? Let’s get rid of all these things’.”

“I can’t believe that this world can go on beyond our generation and on down to succeeding generations with this kind of weapon on both sides poised at each other without someday some fool or some maniac or some accident triggering the kind of war that is the end of the line for all of us. And I just think of what a sigh of relief would go up from everyone on this earth if someday–and this is what I have–my hope, way in the back of my head–is that if we start down the road to reduction, maybe one day in doing that, somebody will say, ‘Why not all the way? Let’s get rid of all these things’.”